Dennis Hayes wrote in Spiked Online, ‘Philosophy for children’ isn’t real philosophy.

(So that I don’t simply repeat myself, go here for my response to the issue of philosophy’s own value: Aeon, should children do philosophy? Also read my response to Tom Bennett’s, Philosophy. For Children?)

My Response to Dennis Hayes

‘Surely the worst, most instrumental reason for doing philosophy is that it might improve your skills in other areas, like maths and reading, while also boosting ‘cognitive abilities’ and pupils’ self-esteem.’ [Dennis Hayes.]

Why?

‘P4C is a popular method of exploring concepts such as fairness or bullying in small group discussions. By claiming that P4C might help all primary-school pupils — especially those on free school meals — to do better in other disciplines, the EEF report does a serious disservice to philosophy.’ [Dennis Hayes.]

Why?

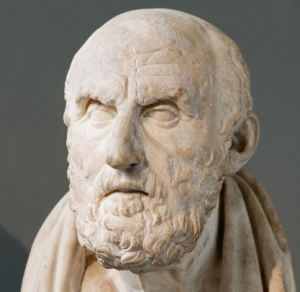

‘The problem today is that children are being taught bits of philosophy, in their circle-time activities. They should be taught more. Why not start with the classical Greek philosophers? Teach your charges about Socrates and Plato and Aristotle! Let them rehearse the arguments of all the great philosophers.’ [Dennis Hayes.]

Why?

‘Childish whining is not philosophy; reading books, even difficult ones, and then having proper classroom chats about them is.’ [Dennis Hayes.]

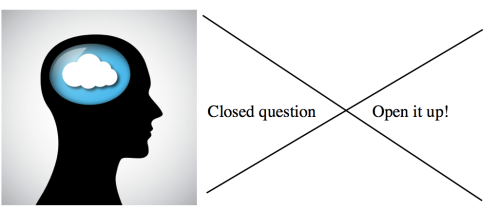

I agree, childish whining is not philosophy. I don’t see much childish whining in my philosophy classes, because I always ask them to say ‘why?’ When someone complains about something without providing good reasons, that’s what I call ‘childish whining’.

‘The EEF report also said teachers don’t know enough about philosophy and aren’t confident enough to teach it. Yet as we wait for a drive to recruit more actual philosophers into primary schools, which we should do, teachers can easily teach some of the history of philosophy in history, and some of the works of philosophy in literature. Even in nursery rhymes there are challenging topics. Why was Humpy Dumpty on that wall? And a burning question for all young girls: Does kissing frogs work? These are potential philosophical sticklers, and can be addressed without the dumbed-down approach of P4C.’ [Dennis Hayes.]

I agree that many teachers don’t know enough about philosophy. Whether a discussion of bullying and fairness are philosophical is all in how it’s approached. A discussion around whether it’s right to bully people (where the teacher holds the view that it is wrong) probably won’t be, but a genuinely open discussion around what bullying is, that leads to conceptual progress in the children’s views as a result of this analysis (see the response to Tom Bennett ‘progess in philosophy’) is much more likely to be philosophical. I have recommended that teachers be trained in what it is they need to be able to run good dialogues with their classes. And what they need – as a minimum, in my view – is an understanding of what a conceptual discussion is and how to facilitate it. For more on this see my response to Tom Bennett ‘It’s (not?) what you know’.

‘The EEF report has been widely welcomed, but largely as a convenient shortcut away from serious teaching in favour of therapeutic talking shops. If we really want the best education for children, then we should ditch classes on jargon and go back to teaching real subject matter — including sometimes difficult, philosophical subject matter.’ [Dennis Hayes.]

Again: Why?

I agree, there is a danger that philosophy is used as a ‘therapeutic talking shop’, but this is purely down to proper education and training about what philosophy is and how it works. Philosophy is not therapy. When working with teachers I sometimes have to explain that ‘feel’ is not a synonym for ‘think’, as it is sometimes used in the classroom. This may have something to do with the fact that teacher training is saturated in psychology and its accompanying jargon. This can be addressed with proper training. For a glimpse (not exhaustive by any stretch) into the kind of facilitation techniques I’m talking about, then go here:

The Philosophers’ Magazine: how to philosophise with children

In conclusion, Dennis Hayes, has an incomplete view of what philosophy is. He clearly thinks that philosophy is ONLY a subject; one that engages students with the classic debates. Let us take, probably the most famous example of a philosopher from the great canon, Plato. He demonstrated, through his dialogues, that philosophy is more than thinking about the canon. Yes, during his dialogues, the characters sometimes engage with the philosophers of the past, but most of the time, they are engaging with each other, with no reference to the canon. But in almost all cases, Plato is showing us how to philosophise, and also providing models for doing so (for example – and it is just one example – the much discussed Socratic method). My approach to philosophy (with adults, children or whatever) is to facilitate a discussion so that it resembles the kind of discussion we might see in a Platonic dialogue. (I do NOT mean: so that it is identical! – Before you write to say ‘do you entrap people like Socrates did?’) I simply mean: so that it contains a similar dialectical structure with similar dialectical aims. This is philosophy as ‘methodology’ that sits next to philosophy as ‘history of ideas’. (There’s also Hegel, Descartes, Spinoza, Aristotle and so on, who also provides methods for conducting philosophical enquiry, all of which are dialectical.) There are even those that say, along Socratic lines, that studying the history of ideas can be done while doing no real philosophy, where philosophy is understood to be an attempt to show whether real-life example X is a genuine example of category Y. Philosophy was practised long before it became a subject at school.