Here’s a lesson plan for Years 6 and up (and able Y5s) on Stoic-related themes for Stoic Week. Draw from it what you want. Taken from Peter Worley‘s forthcoming book, 40 lessons to get children thinking [September 2015].

Equipment needed and preparation: a glass of water, half-filled; handouts or a projection of the extract from Hamlet (optional)

Age: The ‘glass of water’ section is suitable for 7 years and up, but the ‘Hamlet’ section is suitable only for 10 years and up.

Key vocabulary: optimism, pessimism, positive, negative, good, bad

Subject links: literacy, Shakespeare, PSHE

Key controversies: Is ‘good and bad’ a state of mind or a state of the world?

Key concepts: attitude(s), perception, value,

A little philosophy: Stoicism is a branch of Hellenistic (late ancient Greek period from approx. 323-31 BCE) philosophy that derives its name from the ‘painted porch’ (Stoa poikile) in the marketplace of Athens, under which many of the early Stoics taught. The school of Stoicism is said to have begun with Zeno of Citium (c. 334-262 BCE) and been further developed by Cleanthes of Assos (330-230 BCE) and Chrysippus of Soli (279-206 BCE) but the most famous of the Stoics is Epictetus (55-135 CE), originally a slave who later became a free man because of his philosophy, Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE), tutor and advisor to the Roman Emperor Nero, and Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE), himself an Emperor of Rome (who features in the film Gladiator). The word ‘stoic’ has entered the English language and means ‘to accept something undesirable without complaint’. The key ideas of stoicism are as follows:

- All human beings have the capacity to attain happiness.

- Human beings are a ‘connected brotherhood’ and, unlike animals, are able to benefit each other rationally.

- Human beings are able to change their emotions and desires by changing their beliefs.

- Stoics care less about achieving something and much more about having done one’s best to achieve it.

- Stoics attempt to understand what is in one’s power and what is not, to act, when necessary, to change what it is in one’s power to change, and to accept stoically (see above) what it is not in one’s power to change.

Quote: ‘God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; Courage to change the things I can; And wisdom to know the difference.’ (Reinhold Niebuhr’s serenity prayer used by Alcoholics Anonymous)

Emperor Penguin

Critical thinking tool: Examples, counter-examples and falsification – Examples are often used to illustrate a claim whereas counter-examples are examples that are used to refute a claim. Counter-examples are very useful for falsifying general claims:

Child A: All birds fly.

Child B: A penguin is a bird but penguins don’t fly, so not all birds fly.

In this case, because the claim made was a general claim (‘All Xs F’), only a single example is needed to refute it; it is quite unnecessary to mention ostriches or kiwis for the refutation to be successful. Hamlet’s

Is the glass half full, or half empty?

Session Plan: Part One: The Glass of Water

Half fill a glass of water and place it in the middle of the talk circle so all the children can see it. Then ask the following task question:

Task Question: Is the glass half full or is the glass half empty?

Nested Questions:

- Is there an answer to this question?

- Is it a matter of opinion?

- Can it be both?

- Is it good or bad that the glass is only half full/empty?

Allow a discussion to unfold around this question. At some point it may become appropriate to introduce the following words:

- Optimist

- Pessimist

Find out if anyone has heard these words before and see if anyone can explain the words to the class. Provide the following starting definitions if they don’t do so themselves:

- An optimist is someone who sees things in a positive way; someone who often sees the good side of things.

- A pessimist is someone who sees things in a negative way; someone who often sees the bad side of things.

Questions:

- Which one, the optimist or the pessimist, would see the glass as half-full? Why?

- Which one, the optimist or the pessimist, would see the glass as half-empty? Why?

Task Question: Is it better to be an optimist or a pessimist?

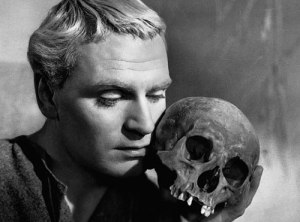

Laurence Olivier as Hamlet

Part Two: Hamlet’s Prison

Part one makes a good session by itself. Here is a second part that is more advanced and can be approached in one of two ways: either use the full extract from Hamlet and allow the class to unpack it or simply skip straight to the central Hamlet quote (‘For there is nothing…’). The previous enquiry around the glass of water should give the class what it needs to approach the quote on its own. I recommend not explaining how the two parts link; give the class the opportunity to make the link. Because you want to get to the thinking aspect of the session I recommend not having members of the class read out the extract. I usually ask them to read it, dramatically, in pairs to each other; I then read it properly to the class as a whole and ask them to raise their hands if:

- There is a word they don’t understand.

- There is a phrase they don’t understand.

- They would like to say what they think the entire extract is about.

- They would like to say what a particular part means.

Give out the handouts or project the extract on the IWB then read the following:

This extract is taken from the play Hamlet by William Shakespeare – it’s the one that contains the line ‘To be or not to be, that is the question’. This is another extract from the play that is less well-known but really good for thinking with.

| HAMLET |

Denmark’s a prison. |

| ROSENCRANTZ |

Then is the world a prison? |

| HAMLET |

A goodly one; in which there are many confines, |

|

wards and dungeons, Denmark being one of the worst. |

| ROSENCRANTZ |

We think not so, my lord. |

|

| HAMLET |

Why, then, ’tis no prison to you; for there is nothing |

|

either good or bad, but thinking makes it so: to me |

|

it is a prison. |

| ROSENCRANTZ |

Why then, your ambition makes it one; Denmark is too |

|

narrow for your mind. |

| HAMLET |

I could be bounded in a nut shell and count |

|

myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I |

|

have bad dreams. |

Once you have spent some time unpacking the extract write up or project the following claim made by Hamlet:

| HAMLET |

Why, then, ’tis no prison to you; for there is nothing |

|

either good or bad, but thinking makes it so: to me |

|

it is a prison. |

(If you are skipping to the single quote then write up just this:

HAMLET …for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so…)

First of all ask the class: What do you think Hamlet means by this?

Then ask the following task question:

TQ: Do you agree with Hamlet – is it true that there is nothing either good or bad, but that thinking makes it so?

Ask the class to come up with some examples of things that are good or bad whatever you happen to think about them.

What about these situations (use these examples only if the children do not find their own):

1) You fail an exam.

2) You win the lottery.

3) Your family forget your birthday.

4) Your tattooist misspells a word in your tattoo.

5) Your favourite pet dies.

6) You discover that you have become addicted to something.

7) You are diagnosed with a terminal illness.

Take some quotes from below and ask the children to respond critically to them. This is done by simply asking them if they agree or disagree with the quote. I sometimes ask for ‘thumbs up’ if they agree, ‘thumbs down’ if they disagree and ‘thumbs sideways’ if they think something other than agree or disagree.

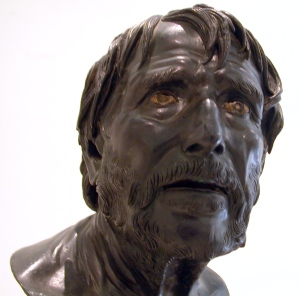

Epictetus

Epictetus

“It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.”

“The key is to keep company only with people who uplift you, whose presence calls forth your best.”

“People are not worried by real problems so much as by imagined anxieties about real problems.”

“There is only one way to happiness and that is to cease worrying about things which are beyond the power of our will.”

“Wealth consists not in having great possessions, but in having few wants.”

Seneca

Seneca

“Most powerful is she who has herself in her own power.”

“Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.”

“Difficulties strengthen the mind, as labour does the body.”

“As is a tale, so is life: not how long it is, but how good it is, is what matters.”

“Life is like a play: it’s not the length, but the excellence of the acting that matters.”

“It is the power of the mind to be unconquerable.”

“A sword never kills anybody; it is a tool in the killer’s hand.”

“Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false and by the rulers as useful.”

TQ: Can one agree with Seneca and also believe in God?

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius

“You have the power of your mind – not outside events. Realise this, and you will find strength.”

“The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts.”

“Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.”

“When you arise in the morning think of what a privilege it is to be alive, to think, to enjoy, to love…”

“Our life is what our thoughts make it.”

“Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking.”

“Reject your sense of injury and the injury itself disappears.”

Extension activities:

Here is a new Thoughting that could be used for, during or after this session that will introduce the children to some more isms.

(Preparation: half fill a glass of water and place in on a table in front of your class. Then, as you reach the part where the speaker in the poem says ‘cheers!’, pick up the glass of water and drink it. Half fill it once more and replace it before beginning the discussion.)

The Glass of Water

The pessimist says it’s half empty

The optimist says it’s half full

The sceptic says, ‘Now, hang on a minute!

Do we know that it’s there at all?’

The cynic says, ‘Whatever you do, don’t drink it!’

The paranoiac says, ‘Who put it there?’

Then, looking round, adds, ‘And why?’

The psychologist says that you think it,

The realist: ‘Without it you’ll die.’

And while all the company debate it,

Over the din no one hears,

When – feeling somewhat dehydrated – I say,

‘Cheers!’

Questions:

- If you don’t already know, can you guess what each of the ists and so on means from the context of the poem? E.g. What’s a pessimist? What’s an optimist? A sceptic? A cynic? And so on.

- Are you any of them? Why or why not?

Related Resources:

“As the weeks have progressed I have noticed real improvements in regards to how the children respond to one another when they disagree and the quieter children are really beginning to ‘find their voices’. One particular child who finds writing a real struggle due to language barriers was so inspired following a poetry session that he sat and wrote a mainly phonetically correct poem of his own!”

“As the weeks have progressed I have noticed real improvements in regards to how the children respond to one another when they disagree and the quieter children are really beginning to ‘find their voices’. One particular child who finds writing a real struggle due to language barriers was so inspired following a poetry session that he sat and wrote a mainly phonetically correct poem of his own!” For this World Poetry Day, download and use this free resource taken from one of our multi-award winning books The Philosophy Shop, to get your children writing some philosophical poetry of their own.

For this World Poetry Day, download and use this free resource taken from one of our multi-award winning books The Philosophy Shop, to get your children writing some philosophical poetry of their own.